How Lead Solder was banned from plumbing

The use of lead to convey drinking water dates to the Roman Empire (the word plumber comes from the Latin name for lead – “plumbum”, hence its chemical symbol – Pb). Not surprisingly, the use of lead bearing solders to join copper water lines was the accepted approach for decades. By far the most common lead-bearing plumbing solder was 50/50 (nominally 50% tin and 50% lead).

Research however indicated excessive exposure to lead in drinking water could result in physical and mental development issues in children. Adults with long term exposure could develop kidney problems or high blood pressure.

Studies showed lead content in drinking water was influenced by several factors. Water PH is lower (more acidic) in certain parts of the country. These areas tended to show higher water lead levels. Also water tests indicated lead levels were higher in new construction, especially during the morning “first draw” of water sitting in pipes overnight.

The issue was addressed at a 1984 EPA Seminar that focused on the effect of plumbing materials on drinking water quality. A conclusion was that a prevalent lead source was lead/tin solders, and lead as an acceptable material for drinking water lines should be removed from plumbing codes.

This culminated in a Federal law change; “The Safe Drinking Water Act Amendments of 1986“. This law prohibited use of lead solders, pipes, and flux in drinking water systems. Plumbing solder lead content was set at 0.20% maximum. It also included wording to require states to enforce the provision.Seemed pretty straightforward – but there was some industry push back. Many plumbers questioned the extent solder contributed to the lead hazard. Also, solders like 50/50 were easy to work with as the melting range allowed plumbers to “cap” and wipe a finished joint. Unfortunately the melting characteristics of available lead-free alloys left much to be desired. Since plumbers had used lead solders their entire career they were reluctant to change.

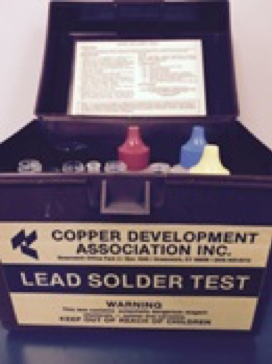

Plumbing inspectors trying to enforce the law had difficulty identifying whether finished solder joints were lead free. As a result many plumbers ignored the ban. To improve inspection accuracy the Copper Development Association assembled a lead solder test kit. Inspectors would scrap a small amount of solder from the joint, put it a test tube, add provided chemicals, and look for a color change indicating lead presence.

Fortunately the transition was facilitated by development of new composition lead-free solders. Chief among them was Harris Bridgit®. These new solders were formulated to better match the preferred flow characteristics of the old 50/50.

Plumbers today routinely use lead-free solders with little thought of the industry change outlined above. Their only link to the past is in the origins of their name.

Bob Henson is the Technical Director for The Harris Products Group and has over 40 years of metal joining experience. He has authored or co-authored several patents and has had numerous published articles.

Bob is active in many industry organizations and committees. He is a Life Member of the American Welding Society, (AWS), and chairs the A5H committee that writes brazing filler metal and flux specifications. Bob is also a member of the AWS Brazing Manufacturers Committee, the US Technical Activities Group that reviews International ISO brazing documents, and the AWS A5 Committee on Filler Metals that reviews specifications for arc welding electrodes, gas welding rods and other filler metals, covering both ferrous and nonferrous materials. Bob serves on the National Skills USA HVACR Technical Committee and is the event chair for the Skills HVACR brazing competition. He is an RSES member and part of the RSES Manufacturer’s Service Advisory Council.